A Catastrophe for Houston's Most Vulnerable People

Within cities, poor communities of color often live in segregated neighborhoods with higher flood risks. This is especially true in Houston.

At least five deaths and dozens of injuries have been attributed to Hurricane Harvey, as it pummeled parts of the Houston region with 24 inches of rain and swirling winds. The storm has now been downgraded to a tropical storm, from a Category 4 at its height, but the catastrophic flooding is only expected to intensify as rains continue, according to the National Weather Service.

Like in the case of previous disasters like Katrina and Sandy, the heaviest cost of Harvey’s destruction is likely going to be borne by the most vulnerable communities in its path. Humanitarian aid organization Direct Relief has created interactive ESRI maps that show exactly where these communities are. Here’s what disaster historian Jacob Remes tweeted out about Harvey:

6. We will hear claims about how disasters don't discriminate by race or class. This is a lie. Because disasters are social, they do.

— Jacob Remes (@jacremes) August 27, 2017

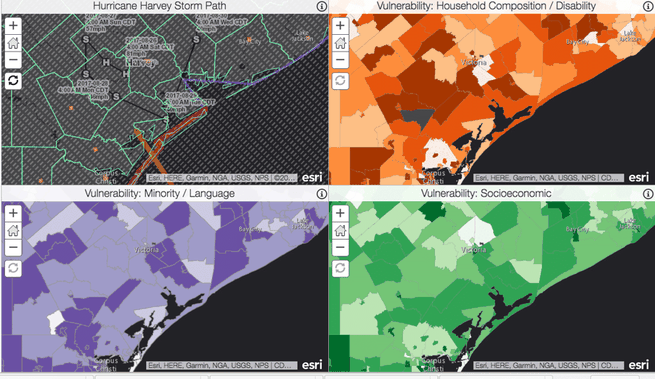

The mapmakers have used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s social vulnerability index to show the geographic distribution of households with elderly or disabled members (in orange), immigrant and limited English-speaking populations (in purple), and pockets of poverty (in green). The darker the color, the higher the concentration of these factors in each region:

Click through for a closer look.

While many South Texans evacuated North per the recommendation of Governor Greg Abbott, poorer or disabled residents may not have had the resources or the capability to follow that advice. Many undocumented immigrants, as well, may have chosen to stay behind because Border Patrol refused to suspend its checkpoints during the storm. (The governor did affirm, however, that shelters will be exempt from immigration enforcement.) Some inmates were evacuated, while others are weathering the storm in place.

Within cities, poor communities of color often live in segregated neighborhoods that are most vulnerable to flooding, or near petrochemical plants of superfund sites that can overflow during the storm. This is especially true for Houston—a sprawling metropolis, where new development has long been spreading thinly across prairie lands that help absorb excess rainwater. And it’s long been understood that the city is unprepared to handle the effects of a storm as unprecedented as this one.

Mayor Sylvester Turner did not ask the city’s residents to evacuate, and in a press conference, he defended that decision.“You can’t put—in the city of Houston—2.4 million people on the road,” he said. But as rain continues to lash down, and the water levels rise, city services have been completely overwhelmed with phone calls and desperate tweets asking for help. Some of the city’s homeless people took refuge in low-lying spaces under highways before the storm hit; Many of these areas are now completely submerged. Boats have been dispatched to rescue those in the city stranded by the flood.

It’s also worth noting the plight of communities that live in more remote parts of the state, where rescuers may take a while to reach in the aftermath of the storm. Residents of many “colonias”—small, poverty-stricken neighborhoods near the U.S.-Mexico border—are directly in the path of the storm. Their homes are often built on flood zones and lack wastewater infrastructure. More than 70 percent of colonia inhabitants are U.S. citizens.

Border Patrol keeping checkpoints open during #HurricaneHarvey. https://t.co/PG3kDhskvr Meanwhile, dozens of colonias are in path of storm. pic.twitter.com/cRIEWjvX09

— Teddy Wilson (@reportbywilson) August 25, 2017

Texas is among the states that are particularly vulnerable to climate change, and it’s well-acquainted with the devastation floods can cause. But it was particularly ill-equipped to deal with a storm of this magnitude: the state has devoted little money and effort towards flood-control planning. As Harvey continues to wreak havoc, it’s clear that the most vulnerable Texans are going to pay the price.

This post appears courtesy of CityLab