The Other Coachella: What You Won't See at the Music Festival

I recall the first time I heard someone in New York talk excitedly about plans to “go to Coachella.” What? I thought.

The Coachella I had known while growing up in the vicinity was a small desert town where irrigation made farming possible, and where the crops ranged from rows of vegetables to groves of citrus and date-palm trees. Under the blasting desert sun, its motto—“The City of Eternal Sunshine”—seemed a literally accurate description, except maybe for the nighttime hours. Every year the next-door town of Indio would hold the National Date Festival, where events included naming a Queen Scheherazade and her court. (That tradition continues: here’s the current queen, Keanna Garcia.) During Cesar Chavez’s heyday as an organizer, his United Farm Workers led a number of strikes and other actions among the mainly Latino work force in the area.

So to me, the name Coachella had always meant “date palms” and “farm-workers’ efforts.” But over the past 20 years, it has come to mean “Music Festival” to much of the world. In fact, the web address coachella.com takes you directly to festival information, rather than to a municipal site.

This tension—Coachella the real place, where struggles for economic and environmental progress have been waged for decades, versus Coachella the stylish venue toward which festival-goers are flocking right now—is the theme of an intriguing new “story map” produced by the novelist Susan Straight, the photographer Douglas McCulloh, and our friends* at the Esri corporation, of Redlands, California. The map is here, and a few details about it are after the jump.

Susan Straight grew up in Riverside, California, in the same county as Coachella, and still lives there. She has written novels mainly set in inland California—The Gettin Place was the first of them I read and admired. She wrote the narrative for this story map, “In the Valley of Coachella,” to accompany the dramatic pictures by Douglas McCulloh and the sequence of aerial photography and illustrated, interpretive maps. The narrative is organized around intersections of Coachella’s “president” streets, named for presidents from Washington onward.

In the description of the woman in the photo above, Straight writes:

At Brown Date Garden, palmeros will climb the date palms and put paper bags on the ripening fruit in August. This part of the valley is called One Hundred Palms, and the palmeros will go up one hundred feet of ladder with the paper bags, in one-hundred degree weather. In March, they’ve just finished the harvest, cutting each heavy bunch of dates with a knife fashioned out of steel, lowering each bunch on a hook to a man waiting at the bottom.

The first time we visited Brown, in 2012, Big Donna Fish corrected me: “It’s a garden – not a grove, not an orchard,” she says firmly. Standing under her canopy of fronds, she said matter-of-factly, “I’ve never seen a gringo go up a palm tree. Never.”

The first date palms were imported from Algeria to the valley in 1903. Presently there are 7,000 acres of date palms producing one of the most expensive, time-consuming crops in America.

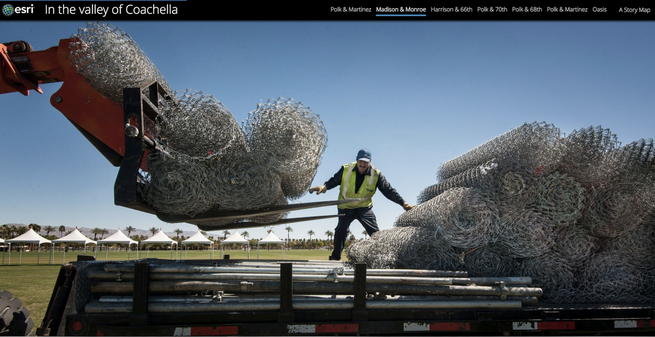

And, another photo, of Jose Arroyo preparing fencing for the music festival:

The whole production is very much worth checking out — above all, if you’re at the festival, have been before, are considering going in the future, or are at this moment getting off a plane at the Palm Springs airport, Coachella-bound. Congrats for this view of Americana to Susan Straight, Douglas McCulloh, Allen Carroll of Esri, and their colleagues and collaborators.

* For the record, about “our friends” at Esri: For many years I’ve known the founders of Esri, Jack and Laura Dangermond, whose historic $165 million gift to preserve a huge stretch of coastal land in California I wrote about several months ago. Allen Carroll and others at Esri also worked with me and my wife, Deb, on maps for early posts in our “American Futures” series in the Atlantic, which led to our forthcoming book Our Towns.